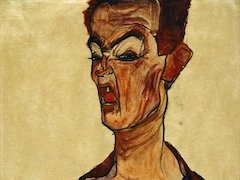

Death And The Maiden, 1915 by Egon Schiele

The long, rising curve of the man's back seems to mimic the idea of the upward rising of some great geological formation. That back is the world in its primal making. The two of them, utterly bonded and at one in their aloneness with each other, float above those hills, on that rucked fling of white fabric, as if this is some kind of a dream of what is happening to them. Is this a tragic clinging to life's only certitude: death?

The painting also puts us in mind of the circumstances of Schiele's own life at this moment. He is on the eve of conscription. Perhaps then the mood of this painting is being tainted and informed by the thought that he is being spirited away into the arms of death. He has also just chosen between two women in his life, with great callousness. One he has married, the other, a model of long standing, he has abandoned.

There is therefore a tremendous tension about all this clinging and cleaving. The figures themselves are pure, distilled essence of Schiele: that slightly awkward boniness; the tapering fingers. Schiele's human bones often tend to look twiggy, over-extended and often even badly assembled, as if they might all of a sudden fall apart at the mighty clap of god's hands. There is often a strange wrenching and writhing about the way in which one human relates to another, as if nothing will ever be settled. He was often inclined to paint or draw human beings in pairs, writhing around and through each other like reptiles.

After his marriage, his portraiture began to look more calm, more serene, less tortured, the human body itself a more wholesome subject altogether, less clinging to life as if to the spar of a boat in mid-ocean. Not so here. The embrace here is a strangely unsatisfactory one: repulsion and embrace all in one. Perhaps it is as much a matter of necessity rather than desire. No one can outlive the claims of death.