Egon Schiele: his life and paintings

Austria's position within the maelstrom of twentieth-century cultural and political history is extremely ambiguous: at once central and off the beaten track. The small nation that came into being after 1918, almost wholly devoid of international presence, was easily subsumed into Hitler's Reich in 1938. On the losing side in both world wars, Austria was further obscured by a tendency to write history from the perspective of the victor nations. In art, this meant that the trajectory of modernism was traced from prewar France to postwar America, with an overriding emphasis on formalist innovations. Germany's more figural Expressionism was grudgingly acknowledged but never embraced. Austrian modernism - which combined Expressionist elements with traces of Symbolism and Art Nouveau - was for many years wholly ignored in the West.

This began to change gradually in the 1970s, as American and British scholars woke up to the bizarre concentration of multifaceted talents who had occupied the Viennese capital in the first two decades of last century. Fin-de-siecle Vienna has since acquired legendary status in interdisciplinary cultural studies. Histories of modern Austrian art generally begin with the architectural boom that swept Vienna in the second half of the nineteenth century. During this period of strong economic growth, the Emperor Franz Josef constructed a necklace of public edifices along the broad Ringstrasse that encircles Vienna's inner city, prompting artists to flock to the capital from all over to compete for decorative mural commissions. The most renowned painter of the era was Hans Makart, but the young Gustav Klimt also earned his reputation executing commissions on the interior walls of structures such as theaters and museums. The favored style combined a sort of blowsy eroticism with a firm grip on classical and historical allegory. Starting from his masterpiece The Kiss, Klimt gradually moved away from the accepted formula, however, evolving a personal symbolism that was less conventionally readable as well as more overtly sexual. This combination proved devastating so far as the tasted of staid Vienna were concerned: Klimt was banished from the ranks of public muralists, and henceforth had to seek support solely from well-heeled private patrons. As cofounder and first president of the Vienna Secession, Klimt remained the most successful artist of his day. Nonetheless, being exiled from the public to the private sector rankled him for the rest of his life.

Egon Schiele was born into this peculiar atmosphere on June 12, 1890. With public patronage on the wane and the commercial gallery system still in its infancy, Klimt and his colleagues had cobbled together a fairly impressive network of private patronage, capable of financing not only the Secession's magnificent exhibition hall, but the efforts of the notoriously inefficient Vienna Workshop, a design collective that endeavored to unite the fine and the applied arts. The Secession's showings of foreign art introduced to Vienna a rather skewed view of modernism, one that placed more emphasis on international Symbolism than on the French Impressionism which had such a decisive influence almost everywhere else in Europe. Edvard Munch and Van Gogh, rather than Manet and Monet, became the dominant role models. This caused Austrian art to grow ever more brooding and introspective just at the moment when its financial support system was in a state of extreme flux.

All his life, Schiele yearned to create the sort of grand allegorical murals that Klimt had once painted, but there was no public outlet for such works and private clients rarely bought them. Unlike Klimt's society portraits, those painted by Schiele and his Expressionist colleagues were unflattering, and few patrons were eager for sittings. Thus a huge void developed between Schiele's artistic desire and his realistic prospects - a gap that was to haunt his entire brief career.

Egon Schiele's family environment was not particularly encouraging for a fledgling painter. Adolf Schiele, the artist's father, was the stationmaster in the small town of Tulln, about eighteen miles west of Vienna, and it was expected that his firstborn son would follow him into railroad service. Little Egon's obsession with drawing trains - which supposedly began at the age of one-and -a-half-led Adolf to hope that his son might become an engineer. Certainly he never dreamed the boy would instead want to be an artist, or, for that matter, considered this a fitting career. Education being fundamental to a bourgeois profession, Schiele was sent off at the age of eleven to attend a Realgymnasium in the town of Krems, some twenty-five miles distant from Tulln. The boy's loneliness and general lack of interest in academic subjects, however, made of him a poor student. Private tutors and a different Gymnasium did nothing to reverse the situation. Indeed, by the time Egon was fourteen or fifteen, he had been left back several times and was some two or three years older than most of his classmates. Matters were hardly helped by the death in 1904 of Adolf from syphilis, which he had contracted around the time of his marriage.

The circumstances of Adolf Schiele's illness precipitated a drastic drop from the family's previously middle-class station. Several years of increasing madness and supposedly the loss of all his savings preceded the father's death. Marie Schiele, his widow, was forced to turn to wealthier family members for assistance, in particular to her brother-in-law, Leopold Czihaczek, who became co guardian of the two minor children, Egon and his younger sister, Gertrude. An older sister, Melanie, went to work for the railroad in order to augment the family's finances. Marie was encouraged by all her relative to consider Egon's artistic ambitions woefully impractical - indeed, selfish and inconsiderate. Yet he was doing worse than ever at the Gymnasium, and toward the end of the spring semester in 1906, his teacher politely suggested he leave. With this, all thoughts of an engineering career - or any profession requiring a university education - had to be abandoned. Egon now prevailed upon his mother and Czihaczek to permit him to apply to the prestigious Vienna Academy of Fine Arts. That summer, he took and passed the rigorous entrance exam - becoming, at sixteen, the youngest student admitted to his class.

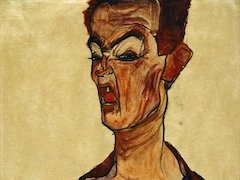

Though passionate about art, Schiele proved surprisingly resistant to the strict regimen at the Academy of Fine Arts. Certainly he was a brilliant draftsman, capable of executing in minutes assignments his classmates slaved over for hours. yet there is something ponderous and heavy-handed about Schiele's early academic studies of antique casts and his relatively soulless renderings of professional models. It is not impossible to understand why his professor never gave him a grade higher than "satisfactory" for these efforts, particularly as the student's attention bean to focus increasingly outside classroom. The influence of Gustav Klimt became somewhat evident in the younger artist's work around 1907, and emerge full-blown in 1908, presumably in the wake of large exhibition the "Kunstschau" (Art Show), which included a roomful of Gustav Klimt paintings. By 1909, Schiele was strutting about Vienna calling himself the "Silver Klimt," and, in flagrant defiance of Academy regulations, had accepted invitations to exhibit at a second "Kunstschau" and at a commercial gallery, the Kunstsalon Pisko. Declaring their opposition to the Academy's rigid rules and orthodox methods in a formal letter of protest, Schiele and a group of like-minded classmates, the self-styled Neukunstgruppe (New Art Group), withdrew from the school on the spring of 1909.

By early 1910, Schiele appeared well on the way to establishing himself professionally. Not yet twenty years old, he had already developed his own distinctive Expressionist style and was amassing an impressive group of supporters, including not just Klimt but also Klimt's Wiener Werkstatte colleagues, the art critic Arthur Roessler, and a small cadre of well-to-do private collectors. So seemingly warm was his welcome into the avant-garde Viennese art establishment that his departure from the Academy could be seen less as an act of iconoclastic rebellion than as a smart career move. Schiele may at once point have seen it as such himself, but appearances proved deceptive. The example of Klimt and Wiener Werkstatte had encouraged him to believe that artists are automatically entitled to societal support, regardless of their success or failure in the marketplace. Schiele was not included to be in the least accommodating, either professionally or personally. His decorative commissions for the Wiener Werkstatte - either too abrasive or too sexually explicit - almost invariably went awry, and his portraits were frontal assaults on a sitter's vanity. His profligate habits eventually exasperated his patrons - mostly older men, from whom Schiele expected a fatherly devotion that they were ill prepared to provide. Petty rivalries within the Neukunstgruppe soon forced the artist to confront the bitter truth: he would not automatically be anointed leader of his generation.

Egon Schiele responded to these dashed hopes by turing inward and eventually fleeing Vienna. toward the end of 1910, he began a series of murky allegories exploring his role as artistic visionary. He was increasingly drawn to Krumau, a beautiful medieval town in Czech Bohemia whose crumbling walls evoked for him the noble futility of human endeavor. Schiele had spent the summer of 1910 in Krumau, and in the spring of 1911, he decided to make a permanent move. At first, the artist was deliriously happy, taking the villagers' bemused looks as a sign of adulation. But the provincial villagers were, as it turns out, hardly impressed with Schiele's bezarre manner of dressing or, more to the point, with his unconventional life style. In August 1911, after a nude model was observed posing outdoors, he was evicted from his lodgings and forced to leave town. From the frying pan into the fire, Schiele now went to Austrian village of Neulengbach where, in April 1912, he was jailed on charges of "public immorality" for allegedly exposing minors to erotic works in his studio.

The loss of the original court records, as well as the absence of much unassailable firsthand documentation of Schiele's imprisonment, make it difficult to reconstruct fully the circumstances that preceded the artist's arrest. Obviously, his habit of inviting children to pose contributed to his predicament, although surviving drawings suggest that, especially in the smaller towns of Krumau and Neulengbach, his underage models rarely removed their clothes. Children clearly found the painter - who in many ways still thought and acted like a child himself - a romantic and appealing figure, and his Neulengbach studio quickly became an after-school hangout. Apparently, the trouble started when one of these girls, Tatjana Georgette Anna von Mossig, decided to run away from home and sought refuge with Egon and his lover, Valerie Neuzil. The couple, not knowing how to react, agreed to take the girl to her grandmother in Vienna the next day, but when they arrived in the city, Tatjana became frightened and asked to return home. All in all, she was gone three nights, but by the time her father came to fetch her, he had already filed charges of kidnapping and rape against Schiele. Tatjana would ultimately waffle in her testimony, and these charges would be withdrawn, but they prompted the local authorities to launch a full-scale investigation of the artist. A search of his studio revealed a single incriminating drawing tacked to the bedroom wall, which led to the count of public immorality on which Schiele was tried and convicted.

The twenty-four days that Schiele spent in jail formed a turning point in his brief life. Hereafter, he was gradually compelled to come to terms with the demands that society places on everyone, including artist. He made visible concessions to conventional morality almost immediately: He more or less stopped drawing children and in 1915 broke with Wally and married the gourgeoise Edith Harms. Professionally, Schiele found it somewhat harder to get back on track. His imprisonment, coupled with his protracted absence from the Viennese art scene, had severed the already tenuous ties with many of his original patrons, and his innate independence tended to sabotage his fledgling relationship with commercial art dealers. After moving back to Vienna in 1912, Schiele's progress was further hampered by his insistence on creating large allegorical paintings, but his exhibitions were receiving more favorable notice and he began to attract a new set of patrons, including the wealthy Lederer family and generous collector Franz Hauer.

Egon Schiele's personal path into adulthood was paralleled by changes in his artistic approach. As he grew less self0centered and more outward-looking, his art grew less anguished and introspective. The number of self-portraits diminished, his line became smoother, his manner of modeling more overtly realistic. The female nude had always figured prominently in Schiele's work - as indeed it does in that of many artists. However, whereas in his early twenties he had explored his own ambivalence toward and even terror of sexuality, he now approached the subject from a greater emotional distance. His later nudes were increasingly depersonalized, but his portraits were, conversely, more probing. Instead of projecting his own personality onto that of his subjects, as he had formerly, he was now intimately attuned to each individuals's identity.

The greater humanism of Schiele's later work was conditioned not only by his newfound maturity, but more concretely by his marriage and by his experiences as a solder in the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I. His imminent induction into the army had escalated his flirtation with Edith Harms, whom the artist married four days before he was scheduled to report for basic training. the newlyweds' forced separation and Egon's jealous suspicions of Edith placed an early strain on their marriage. Yet Schiele's need to come to terms with his wife's failings gave him greater insight into the workings of the female psyche overall, as was evidenced in many of his subsequent portraits. He showed similar compassion toward the Russian prisoners of war (ostensibly his enemies) whom he was assigned to guard. "Their desire for eternal peace was as great as mine," he noted. Sensing nationalism's devastating potential, he was an avowed pacifist at a date when so-called radicals still supported the war.

The war of course totally disrupted Schiele's professional life. After completing basic training, he spent some months stationed in and around Vienna, but even thought the artist was often allowed to sleep at home, he could get little painting done. In May 1916, he was sent to the rural hamlet of Muhling, about three hours west of Vienna. His duties - mainly office work - were not particularly taxing, and since Muhling was not in a war zone, Edith was allowed to accompany him there. Nevertheless, the couples' life remained unsatisfactory - 1916 was Egon's least productive year artistically, and Edith, bored and lonely, seems to have complained constantly. Considering that the Austro-Hungarian army provided privileged spots for many artists and writers, Schiele found it surprisingly difficult to wangle a post that would allow him to use his talents. Finally, in early 1917, he managed to get himself assigned back to Vienna, where under the sympathetic eyes of his superiors at the Military Supply Depot, he was given plenty of time to pursue his art.

Egon Schiele returned to Vienna full of creative energy and eager to get his career moving again. Som of his plans - for example, for the establishment of an exhibition organization modeled along the lines of the Secession - foundered, but on the whole he made remarkable strides. The director of the Staatsgalerie, Franz Martin Haberditzl,, acquired a number of works by Schiele and sat for a portrait. The first portfolio of Schiele reproductions was published by the book and art dealer Richard Lanyi, and commissions of all sorts began to roll in. Schiele also took the lead as an exhibition organizer, first for the Imperial Army Museum, and then in 1918 for the Secession. Schiele's own section at the Secession show was almost completely sold out, and though inflation ate into his earnings, the artist for the first time saw a prospect of affluence. In 1917 and 1918, Schiele rented a large garden apartment on the Wattmanngasse, retaining his old premises on the Hietzinger Hauptstrasse with the thought of opening an art school there. Since Klimt's death that past February, Schiele had been widely acknowledged as Vienna's foremost artist.

It is ironic that, with the entire world in a state of momentous transition, Schiele to the end cast himself in the antiquated mold of Gustav Klimt. Although private patronage had for most of his life provided Schiele with meager substance he refused to embrace the wider market place that could only be reached under the auspices of a commercial gallery. Instead, with his new, more humanistic and palatable style, he set himself up to replace Klimt as a society portraitist. And while public patronage was doomed even in Klimt's day, Schiele spent a good portion of his last two years concocting a monumental mural scheme. How - if ever - this self-style mausoleum was to have been built remains unclear. Evidently, however, most of the allegorical nudes which Schiele painted in late 1917 and 1918 were intended for its walls. His final masterpiece, The Family, was not an autobiographical statement, but rather a metaphor for what Schiele, in his mausoleum notes, called "earthly existence." the male figure (a self-portrait representing the life force) hunches over the female (the vehicle) and the infant (the creative outcome). The three figures encompass a nested cycle of decay and regeneration.

Although The Family is not autobiographical ( and the woman is an anonymous model), Egon and Edith did in fact conceive a child shortly after the painting was finished. There is surprisingly little evidence - either artistic or anecdotal - of how Schiele was affected by the prospect of fatherhood. While he was solicitous of his wife's health, his growing professional stature had if anything increased the emotional distance between them. In the autumn of 1918, en early cold snap and pervasive fuel and food shortages provided a fertile breeding ground for the deadly Spanish influenza epidemic that would eventually sweep Europe and the United States, claiming more victims than the world war. Edith, in her sixth month of pregnancy, contracted the disease a few days before her husband. She died on October 28; Egon followed on October 31.

The body of work which the twenty-eight year old Egon Shiele left behind is indelibly marked by the stamp of his youth. His earliest Expressionist pieces chart the universal adolescent search for personal and sexual identity, while the adoption of more conventional stylistic methods accompanies his growing maturity and acceptance of the role of husband and artistic leader. Although it is wrong to conflate Schiele's life with his art, the art probably is more strongly shaped by his personal development than is commonly the case. Unlike many modernists in other countries, Schiele did not have the support of a group of like-minded colleagues. Drawing creative sustenance from an eclectic smattering of foreign and domestic influences, he reached his ultimate formal solutions largely alone. So long as modern art history was written in terms of broad schools and movements, the idiosyncratic achievements of Ego Schiele could never receive proper recognition. Today, however, we are more inclined to recognize that history is a messy mass of loose ends, subject to myriad distortions and subjective biases. From this perspective, Egon Schiele is very much a man of our times, just as his anguish and confusion reinforce our pervasive conviction that there are no easy answers to the existential dilemmas confronting us at new century.