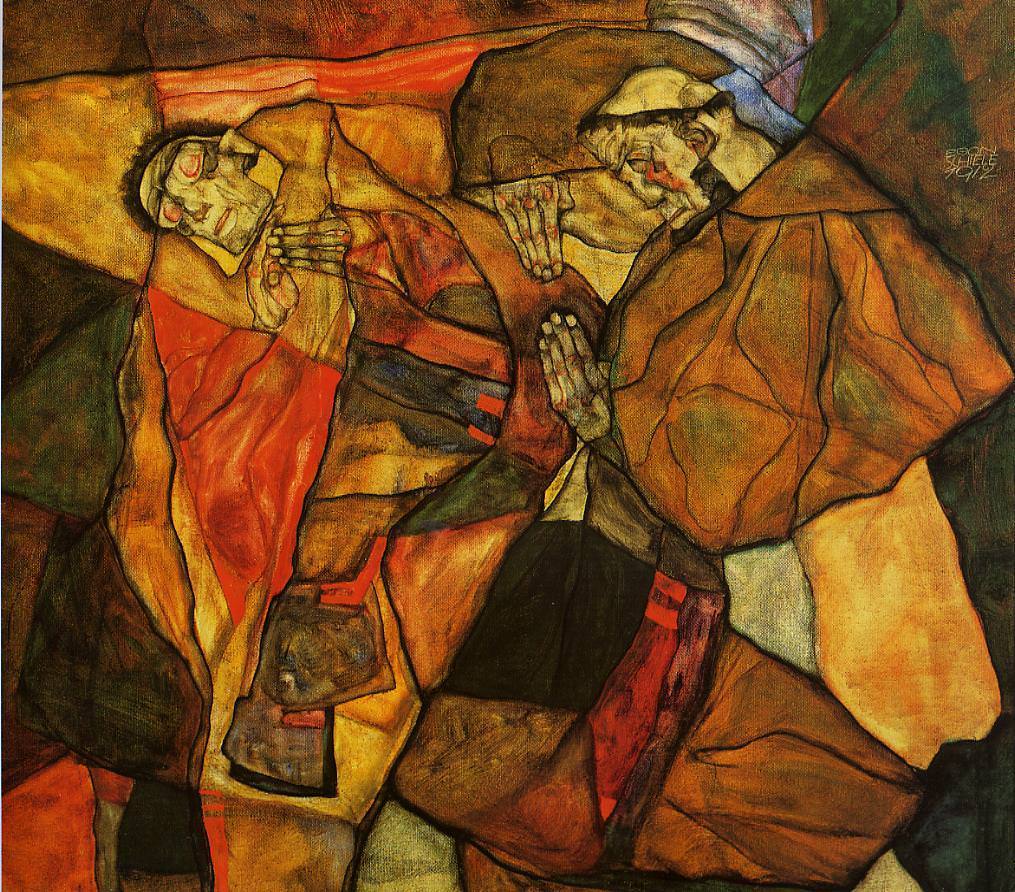

Agony, 1912 by Egon Schiele

Schiele believed that artists are like priests or monks: spiritually enlightened beings whose mission it is to share their special vision with the more ignorant masses. This notion dates back at least to the German Romantics of the early nineteenth century. For Schield, the concept was concretely embodied by the magisterial Gustav Klimt, whose floor-length painting caftan and balding pate gave hime the appearance of a genuine religious sage. Schiele fairly early on got himself a similar robe, so as better to enact the role of disciple.

The relationship between Klimt and Schiele has often been overdramatized by the latter's biographers, and in truth it is difficult to ascertain just how close the two artist were. Did Klimt - who was extremely generous toward all younger colleagues - really show Schiele any more encouragement than he did others? And did Schiele, regardless of Klimt's attentions, truly idolize him as a sort of artistic surrogate father? Klimt's influence, especially on Schiele's early work, is evident, but Schiele also made a point of rejecting the more decorative aspects of Klimt's syle.

In any event, many of Schiele's paintings from the years 1922 through 1913 depict spiritual interchanges between a godlike entity and an acolyte. Schiele characteristically put his own image into these works, usually in the position of the acolyte but sometimes in both roles. Klimt's physical resemblance to a monk has caused some observers to identify him as the senior figure in certain of these pictures, and it is generally agreed that he plays this part in the 1912 canvas the Hermits. Agony appears to be a more generalized interpretation of a similar subject. Neither figure has features that can conclusively be identified with a specific person. Carrying forward the religious metaphor, Schiele believed that artists, like saints, must suffer for their beliefs. Agony, which may well have been painted shortly after he was released from prison, is telling testament to such travails.